Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:10 — 16.1MB)

This audio is 17:10 minutes long.

Eccl. 7:8 “Better is the end of a thing than the beginning thereof…”

Business 101 teaches us to reverse engineer our desired outcome. Business books are filled with verbiage aiming to convey the same message of beginning with the end in mind. It seems so easy, concise and straight-forward. But it’s not.

Starting is hard. Finishing is harder.

That’s true with most anything. Take weight loss (I wish somebody would take my weight and lose some of it). Starting is ridiculously difficult. We may have a very solid idea of where we’d like to end up. Down 20 pounds? Down 50? Down 100? The higher the number the tougher the start. Because the task just seems so daunting.

And then there’s the middle. Let’s not forget the middle. If starting is hard, then the middle is almost certain to sink our chance for success.

The middle is the area that kicks our butt when we’re quite proud of ourselves for starting. Relishing our courage and conviction to get going, the middle grabs us by the throat and jumps in our face screaming, “NOT SO FAST!”

The bravest among us shrink in the middle. And the middle just goes on and on, seemingly a never ending area camouflaging the finish. It’s in the middle where we wonder about the ending. We can’t see the finish. Not knowing how close, or how far away we are, many of us quit smack dab in the middle. The famous story of long distance swimmer Florence Chadwick illustrates the point beautifully.

On July 4, 1952, at the age of 34, Chadwick attempted to become the first woman to swim 21 miles across the Catalina Channel, from Catalina Island to Palos Verde on the California coast. The weather that day was not auspicious-the ocean was ice cold, the fog was so thick that she could hardly see the support boats that followed her, and sharks prowled around her. Several times, her support crew used rifles to drive away the sharks. While Americans watched on television, she swam for hours. Her mother and her trainer, who were in one of the support boats, encouraged her to keep going. However, after 15 hours and 55 minutes, with only a half mile to go, she felt that she couldn’t go on, and asked to be taken out of the water.

Brian Cavanaugh, in A Fresh Packet of Sower’s Seeds, noted that she told a reporter, “Look, I’m not excusing myself, but if I could have seen land I know I could have made it.” The fog had made her unable to see her goal, and it had felt to her like she was getting nowhere. Two months later, she tried again. The fog was just as dense, but this time she made it. After 13 hours, 47 minutes, and 55 seconds, she reached the California shore, breaking a 27-year-old record by more than two hours and becoming the first woman ever to complete the swim.

(quoted from Queen of the Channel website)

Keeping a mental picture of the shore in her mind helped Chadwick accomplish the goal the second go round. Proof that the middle can sink the best of us if we’re not focused, prepared and determined.

Seth Godin talks a lot about the middle in his popular book (well, aren’t they all popular really?), The Dip. Fact is, the book is all about the middle, the area where we’re all tempted to give up. It’s that vexing area where we’re often unsure if we should keep going or turn back. How can you know what to do? Sometimes, maybe most times, you can’t. You just have to make up your own mind about what you’ll do.

Reaching the shore, whether it’s literal like it was for Florence Chadwick, or whether it’s figurative like it is for you, signifies triumph, success and reaching the goal.

It’s the culmination of hard work, dedication and arduous work. At the goal is where we can exhale and enjoy the view, if only momentarily. It’s accomplishment. And it feels terrific!

But it all starts with a beginning. A starting point. And your persistence through the middle is what brings about the finish.

If you think about your career, your challenges and your opportunities – you can even apply this to your life in general, including your personal relationships – there are a variety of starting points.

Think of some current problem. Go ahead. Think of it right now. Think of the biggest problem you face at work.

Is there only a single starting point toward solving that problem or do you have multiple choices? I’m betting you’ve got a few different choices or angles in how you can approach, or start, tackling that problem.

Now think about the one you’re most likely to take? Why? Surely you’ve got a reason why you’re picking that starting point. What is it?

You’re clearly convinced, based on what you know today, that this choice – this starting point – is the best approach. Great.

What do you need in order to start? Maybe you need to convince somebody else that this approach is best. Maybe you just need to inform the troops of the where, how and when you’re going to get going. Whatever it may be, there are some pre-launch sequences we all have to prepare. So you’ve done that. Now it’s time to start.

You take a step, maybe two. Maybe more.

Is there anything that will deter you from moving forward until you hit your target? Sure. New information might change your mind. That could come in the form of new information you didn’t have before you started. That new information would have caused you to take a different approach. So, you stop what you’re doing, regroup and begin again…this time approaching the problem with new information.

New information could also come in the form of feedback on your current action. Maybe you thought you’d be seeing some improvement by now, but instead, things are getting worse. What you thought would solve the problem is only making it worse. Armed with this new intel, you go back to the drawing board to begin again.

There are a myriad of things that could cause you to change direction, but are they always rational? Logical? Measurable?

No, sometimes we just get antsy and decide to try something else. It’s that something else that can kill initiative and momentum. Too often it’s the antsyness or lack of focus and concentration that foils our success.

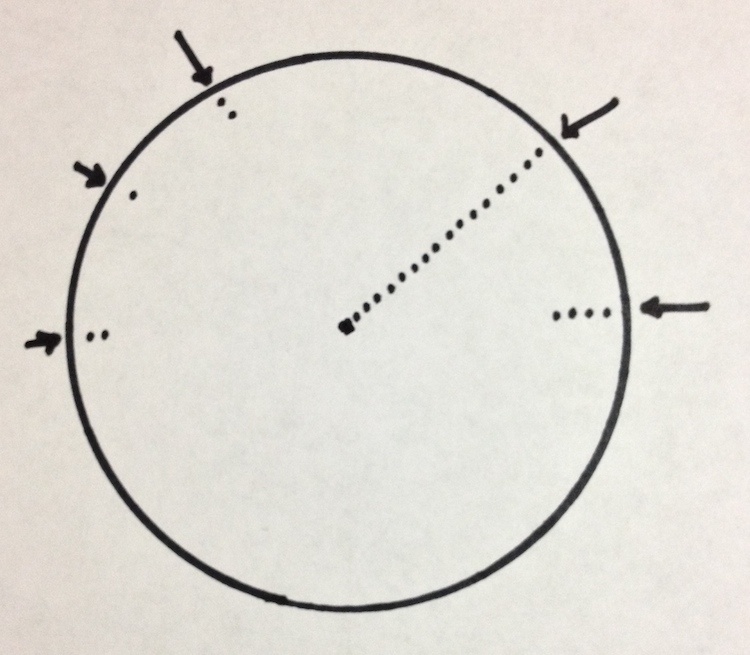

Draw a circle with a dot in the middle and let the dot represent your target, goal or objective. You’ve now got 360 starting points (that’s how many degrees comprise the circle for you folks that are dumber at math than I am). That’s a lot of choices. The problem I’ve just defined could be represented by putting a dot on the circle – anywhere you’d like – and letting that dot represent your starting point. Now put a dot for each step you’ll make toward the center, the goal. After you put down three dots, stop. Now, put a dot somewhere else on the circle, representing a new starting point. You have to start the process all over. Those three steps you took from the first starting point may or may not be lost as far as learning goes, but they’ve certainly cost you something. Maybe just time. Now from this new dot or starting point you can plot a dot at a time toward the center or the goal. But wait, all of a sudden you’ve got a better idea. A different starting point. So you stop everything and plot yet a third dot (starting point) on the circle…far away from the other starting points. And the process starts all over again.

Does this describe your work? Do you find yourself starting and stopping, replotting the course and starting again? It’s fairly common in some workplaces. The starting goes fine. It’s the sticking with it that’s hard. Always searching for a better course rather than staying the course they’ve begun. Some leaders need to keep searching for smarter answers, better solutions. They spoil their own success sometimes because they overthink it and want to outsmart themselves (and others).

It’s often the plight of the jack rabbit start. Over and over again. Have you ever been sitting at the front of a stop light next to a driver who was clearly more anxious than you to get to the next light? They peel out racing down the road toward the next major intersection. You resume a steadier speed. Seconds later you approach the next stop signal and there he is. Speed Racer is sitting right beside you again. For all his acceleration from that last signal light, he didn’t advance past you. He just burned more fuel getting there.

Now, imagine his anxiousness getting the best of him and so he turns right. He’s heading the same direction as you, but these stop lights are driving him crazy. He knows another route. Sure, it’s longer, but he’s thinking it’s got fewer stop lights. But he forgot about the railroad tracks along the other path. Oops!!

We’ve all done it. Here in Dallas everybody is familiar with going to the DFW International Airport. Even if you’ve got a toll tag – a device that electronically allows you entry and exit without stopping to pay because it will automatically bill you – there are many lane choices. Just like a grocery store checkout line, all of us sometimes invariably select the slowest line. Sometimes, we jump out of one line into another. Only to find that if we’d stayed put, we’ve have made it to the front of the line faster.

Our impatiences sometimes kills our success.

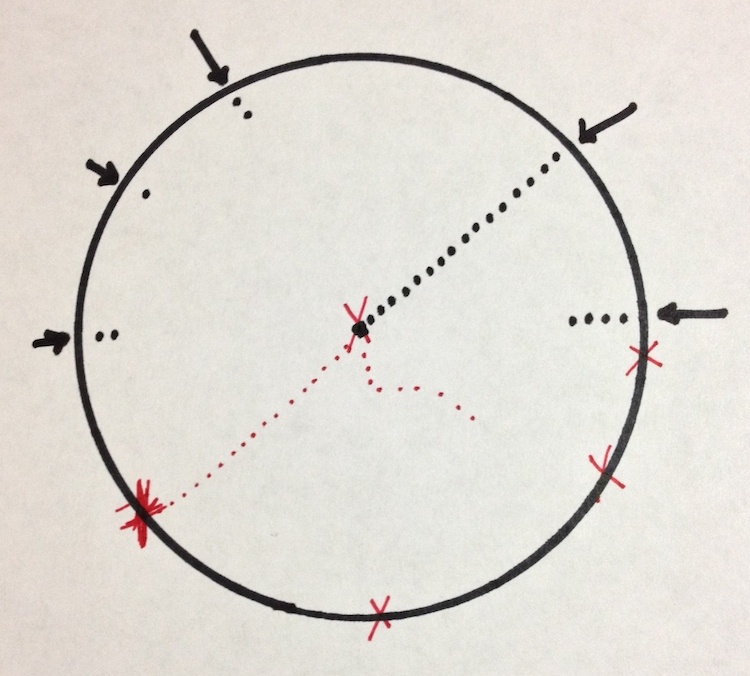

But something else can happen to us, too. Sometimes it’s not all the starting point choices that kill us, it’s the choices of outcome. Remember that circle you were just drawing. Go back to it and let’s reverse a few things. This time, we’re going to make the center dot – the one smack dab in the middle of the circle – represent our starting point. Now we’ve got 360 different outcomes we can select. Each degree on the circle represents success, achieving the goal. Sometimes that more accurately represents our problems at work. We have to decide what we need or want to accomplish. So we plot a dot on the outer circle to represent our target, our goal.

Now, from the center dot we plot dot after dot toward that outer circle point that represents our goal. But wait. We’re not sure about that goal now. Now that we’re four dots away from the center, moving toward the goal, we’re uncertain about things. Maybe that’s not the objective we want after all. There’s another spot on the circle, 45 degrees away that now looks awfully attractive. So we now head in that direction. Our course isn’t nearly as straight as before, but that’s okay. We’re certain this is the result we want more so than that first one. Until we start looking around a bit and like a kitten with a new ball of yarn rolled across the floor, we spot a new area on the circle, about 20 degrees away. It looks better than anything we’ve aimed at. Oh, yes. This new goal is most certainly superior to all the others. And we change course again.

Does that describe your company? Your leadership?

Starting is a bit more challenging this go round because we can head off in too many different directions. That makes starting more difficult than when you’ve only got one target from which to choose. But the problem is similar in that we’re distracted and sometimes we wonder if that other objective would be better. In both scenarios a change of course happens. On one hand, we change how we’re going to get there. The objective never moved, but we altered our starting point and our route to get there. In the second scenario, our starting point never moved, but our objective did. And because our objective moved, our way to get there naturally had to change, too.

Leadership is partly about commitment. It’s not about being the smartest guy or gal in the room. And it’s certainly not about making sure everything thinks so. Leadership is many things, but today’s session is really about one thing, commitment.

It’s about making a decision and not being distracted to steer away from that decision at every turn. Yes, feedback may dictate a change of direction. Yes, new information can reveal we made an initial decision that needs to be altered. But…too often leaders change course without such compelling intelligence. They do it because they’re afraid of being wrong. Or they’re afraid of failure. Or they’re afraid they won’t appear as smart as they’d like. A plethora of reasons serve as excuses for constant course changing.

The problem is bigger than you may think. It’s a problem of confidence. Confidence of your team in YOU and in the direction you’re leading them in.

Just because you lack the ability to stay true to a course until you find out if it will succeed or not doesn’t mean success isn’t possible. Or even probable. One of the things you’ll notice in my crude drawings is how much closer to success you’d be if you hadn’t changed directions. Waffling leaders are no leaders at all.

Does this mean you should be stern, unmoving and unable to change your mind? Not at all. But it means if you’re going to consent to every input you’re doomed as a leader. It means when you’re faced with direct reports who may question the direction you’re going, you deal with that appropriately lest you lose your entire team. It means that tough conversations – even confrontations – may sometimes be required as you demonstrate your commitment to the plan or process. If you’re not committed to it, how do you expect your people to be?

It’s not about weakness. Nor is it about hard headedness. But it is about tenacity to take something from start to finish. From start to success. From start to profit. By showing your team how to work a process with tenacity you’ll achieve higher success than by showing them how adaptable you can be by their every suggestion to do things differently. It’s just one small illustration of the power of committing to both the start and the finish of a thing.