Podcast: Play in new window | Download (27.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

It’s stress. A constraint. A real challenge.

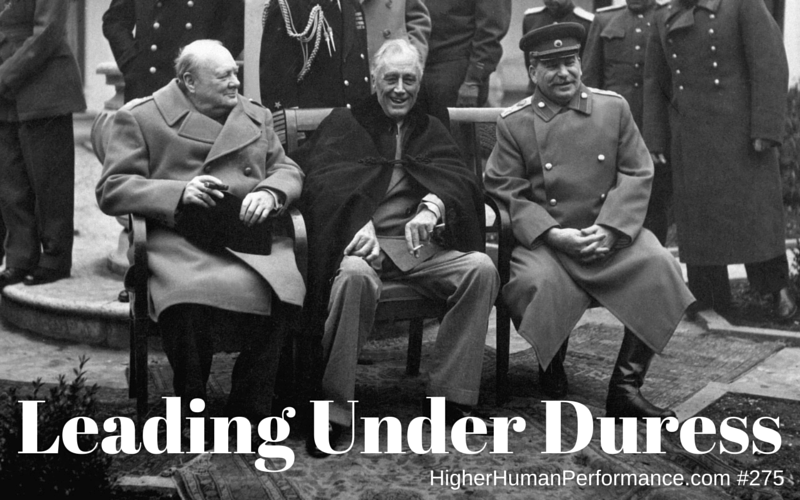

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met at Yalta in February 1945 to discuss their joint occupation of Germany and plans for postwar Europe. Leadership in time of war is among the highest stress leadership anybody can experience. I don’t know firsthand, but how can anything be more stressful? Millions of lives on the line. Entire countries at risk. Enormous financial strain on economies. It’s also when great leaders emerge.

The Many Faces of Duress

Actually, the two faces of it. There are many shades of grey, but let’s just distill duress into 2 groups: internal and external. Internal is the pressure you put on yourself.

Duress can be prompted by something external, but it’s more about you. For example, the student who wants to perform well can put pressure on themselves to score a perfect 100. The exam is the event prompting the pressure, but the exam doesn’t care if you pass it or fail it. The teacher doesn’t likely care if you score a 100 or an 80. But you care. That’s internal duress.

External duress is mostly driven by something putting a demand on you. A board of directors can put pressure on a CEO to elevate profits by at least 10% this quarter. If the company is lagging behind the profit forecast, that may be a tall order that creates lots of pressure for the CEO. Here’s the thing — external duress like this can create a slew of internal duress points. The CEO may start to wonder if the board wants to get rid of him. Duress can morph and adapt like the most vile monster of any horror movie.

Every leader faces both forms of duress at various times. Most leaders are under daily duress. That’s why they’re leaders. They’re people empowered to solve problems and make the harder decisions. If there is no duress, what’s the point of leadership? Better said, if there’s no problem to be solved, no plan to be enacted or no strategy to be implemented — what are you doing here?

The Work Of The Leader May Not Look Like Work At All

“What does he do all day?” asks an employee of a leader. I wonder what the questioner means. Are they implying anything? Do they not think the leader does anything?

Turns out they don’t think she does anything. They never see the work product of their leader. I find that interesting so I dig a little deeper.

“Tell me what you know about her (the leader) work?” I ask. The employee stares off into space. There’s some eye blinking and pursing of the lips. Followed by some shrugging. Eventually, he says, “I’m honestly not sure.”

“Describe her interaction with you, or with other staffers,” I ask. He goes on to tell me about a variety of meetings, mostly held by his boss. Different people are involved in these meetings, but they’re described mostly as “a major waste of time.”

I’m getting nowhere. So I ask, “Tell me some decisions that she makes.” Now we’re getting somewhere. This employee begins reciting a number of decisions – some he thinks are smart and others he’s not quite sure about. This employee doesn’t have a clear understanding of what he’s seeing. He’s young, pretty inexperienced and only 8 months into his career. He’s learning. It gives me an opportunity to serve him by educating him how the world really works. That includes the work of a leader whose work doesn’t always look like work.

Gathering information. Collecting and evaluating evidence. Thinking. Collaborating with others. Deciding. Communicating. Making sure it gets done. These are some of the basic activities of a leader. There may be a report distributed, a presentation delivered or a spreadsheet shared, but the work product of a leader can be much less visible than the work product of the rest of the organization. But if the duress is open enough, visible enough and large enough — the work can be more easily seen.

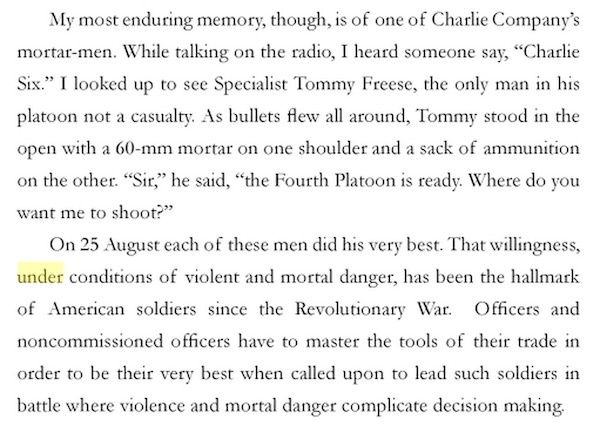

War may be the best illustration. In their book, Leadership: Combat Leaders and Lessons, James Abrahamson and Andrew O’Meara collect the stories of various military leadership. One story is told by retired U.S. Army Brigadier General William J. Mullen III. His story came from the war in Viet Nam.

Flying bullets most certainly complicate decision making. But sometimes in our organizations there are other moments of duress that provide bigger opportunities for people to see the work of the leader. Some rise to the occasion. Others don’t.

Some Have It. Others Just Say, “I’ve Had It.”

Few things determine the quality of leadership more than increased levels of duress.

The very best leaders shine under pressure. They do their best work when the heat is on.

The poorest leaders wilt. Some wilt sooner than others, but eventually all poor leaders give way to the duress.

What makes the difference? My work has led me to see some common denominators in the leaders who excel when the intensity grows. You’ll be quick to see the things that are likely missing in the leaders who fail when challenges get heavy.

These are the qualities I observe in high performance leaders – the ones who perform best under duress…

1. They keep calm.

Panicked leaders are ineffective. Always. Show me an overly excited or emotional leader and I’ll show you somebody who will most certainly crack when the PSI increases.

Calm and deliberate are qualities of the best leaders. In fact, the greater the pressure, the more calm they get. They have an ability – innate or learned, I’m not sure – to counter-react the energy of the challenge. If the challenge intensity grows increasingly hotter and hotter, this leader gets cooler and cooler. The zig and zag of it is something they master. The more the constraint zigs, they zag. The organization responds in kind.

I can spend thirty minutes with most leaders and tell you about their team. If the leader is anxious or nervous, you know their team is going to reflect it. Sure, they’ll be exceptions, but mostly the team will mirror the emotions and the energy of the leader. On the flipside, let me spend 30 minutes with a person who is the right hand of the leader and I’ll likely be able to tell you how the leader is wired. That’s the power of leadership.

2. They’re communicative.

The most effective leaders during troubled times also have a commitment to make sure the team is fully informed. This includes sharing information, but it goes into collecting it as well.

Communication is at least a 2-way street, sometimes more, depending on how many people are involved in the process. Great leaders are great listeners and great investigators. They gather information and evidence. They don’t sit by the hotline waiting for the phone to ring. They’re out knocking on doors talking to people. Imagine the homicide detective who just lets the clues and evidence land in his lap. They’d be fired right away because you’ll never get to the truth sitting on your hands. You’ve got to go get the clues the evidence you need to solve the crime. The great leader knows that they’ve got to go find what they need to solve their problems — and the problems of their organization — so they go chase it. That’s done with communication – talking with and listening to people.

3. They’re candid.

When duress is hammering away, the great leader elevates their directness. All the best leaders I’ve ever known were candid and direct. Even blunt. But when things are tough, they get more direct because they understand the situation.

People expect it when times are tough. For starters, speed matters. During warfare, when bullets are flying, short, loud and direct commands save lives. Troops are trained to take orders partly because when the heat is on our military understand the necessity of instant compliance. Don’t think. Don’t argue. Just do it. When the commander says, “GO!” — you GO. That’s a pretty direct (candid) directive.

Poor leaders struggle to be so direct, even under duress. They want to loiter around in language that is unclear and less direct. I’ve got some theories about it, but nothing I’ve fully vetted enough to hang my hat on. Only suspicions really. Sometimes I’ve seen leaders do this and thought, “They’re working too hard to appear smart. ” I think it can be a problem among the less effective leaders. They’re overly concerned about how they appear. So they spend more time in meandering language. But sometimes I’ve seen leaders who didn’t know what to do so they tried to mask it by using big gobs of business-speak and other ambiguous language. And then there are times when I’ve seen leaders who just weren’t yet committed to a course of action so they talked in waffling language leaving people to wonder what they were saying. No matter the reason, ineffective leaders find it impossible or overly difficult to be as direct and as candid as necessary to elevate the performance of their team under duress.

When the going gets tough, the tough get going. Only if the tough leader can be direct enough to lead the going.

4. They’re open.

That means they’re open-minded. They don’t conclude things before they’ve soberly considered as much data as possible. Sometimes the time constraint is severe giving leaders very little time to consider very much. If a loaded gun is aimed at you, there’s no time to debate. You’d just better react. But if you’re planning a SWAT team arrest of a known felon, then you’ve got some time to craft the strategy that can best keep folks safe.

Great leaders under duress avoid preconceived conclusions or assumptions. Partly because they’re calm and intentional in gathering data, but mostly because they understand the situation. When the pressure is growing the risks grow, too. That makes the decision-making more critical and the margin for error small. That’s why the most effective leaders are open to information, evidence and perspectives.

When George W. Bush was governor of Texas he earned the reputation of being a leader who surrounded himself with bright people. I know the liberal media and comedians had a hay day depicting him as hick idiot, but I think they got it wrong. I don’t care about the politics. Think what you want. Do what you want. But when it comes to leadership under duress President George W. Bush faced something in 9-11 that equals few things faced by sitting presidents of our country. There’s enough evidence to prove he gathered as much information as he could, listened and was open to suggestions and observations. History can determine if he got it right or not, but he did what he had to do with the resources and information available to him at the time.

That’s what all great leaders do. They don’t form a knee-jerk opinion or implement some half-baked strategy. They maintain an open mind to give themselves the best opportunity for a great decision.

5. They demand evidence.

Evidence may not be truth, but it leads to truth. The great leaders elevate this — and all these other traits — under moments of high duress.

Great leaders demand to know more. During stressful times, the leader won’t simply allow a lieutenant to offer an opinion with explaining why they hold that opinion. Or how they formed that opinion.

Poor leaders just accept things on first blush. Somebody reports something and they swallow it, taking it as fact. What if they’re wrong? The downside potential is simply too great for the effective leader. So, they ask questions and probe.

Some time back I was sitting with an executive who was telling me a story of something that had happened inside his company. The right hand person of a divisional manager went to another divisional manager to get some insight. That divisional manager went to this executive to report how odd she thought it was for this person to come to her, instead of her boss. The executive appropriately asked, “How do you know she didn’t?” Well, that stumped the divisional manager. She didn’t know if this person had first gone to his boss or not. She assumed he hadn’t, but was forced to admit that she didn’t know. A very small thing that could have become something bigger except for an effective leader – an executive willing to demand evidence and refusing to let assumptions rule the day.

6. They’re decisive.

This involves a couple of distinct things. One, they don’t waffle. A big part of this involves their ability to distinguish between the fact-finding, data-gathering phase of problem-solving and the decision phase. During periods of gathering and discovery the effective leader is open, doing everything possible to facilitate the best input possible from others. Two, after the decisions is made they don’t back down unless new evidence or facts warrant it.

It’s common to see poor leaders do just the opposite. They’re not open during the gathering phase, often making sure they impose their opinions on the team. That results in people shutting down and not being as forthcoming as they might like. And once the decision is made, the poor leader can change his mind without any new evidence. They just decide they don’t want to do what was first decided. Or they withdraw permission to do something previously decided — but without any real explanation. Poor leaders often have buyer’s remorse in the time between the decision and execution. As a result, you may see lots of starting and stopping, but not much meaningful action.

The truly good or great leader is able to move forward with 80% accuracy and own the decision. There’s always more data to be gathered. More information that might help. More questions to be answered. But duress doesn’t often afford all the time in the world. A decision must eventually be made and great leaders don’t drag their feet to make the best decision possible with the information they’ve got. And they don’t often backtrack that decision unless new information or evidence is presented.

7. They foster confidence.

Because of all these qualities, the great leader is able to use moments of extreme duress to the advantage of the organization. The people on the team of such a leader grow confident in their ability to navigate troubles. A novice sailor can sail clam waters. But when a storm erupts, you want to know the Captain is seasoned and strong. Watching a captain perform in the storm proves their worthiness of the task. Sailors will more likely work for the captain capable of that kind of leadership because he makes them feel safer.

It’s no different on your team. When it hits the fan people look closely at leadership. You have to answer the bell and do well in order to keep the troops performing well. When a leader’s team loses confidence, then the leader is usually — and appropriately — at greater personal risk. Odd isn’t it? When the leader is under the most intense personal duress is when the leader isn’t performing well. There’s a big lesson, and a great place to end today’s show. Step up your game and perform. It’s the best course of action during tough times. Fail and you might as well pack your bags because it can be tough to recover from a poor leadership job when you were needed the most.

Subscribe to the podcast

To subscribe, please use the links below:

To subscribe, please use the links below:

- Click Here to Subscribe via iTunes

- Click Here to Subscribe via RSS (non-iTunes feed)

- Click Here to Subscribe via Stitcher

If you have a chance, please leave me an honest rating and review on iTunes by clicking Review on iTunes. It’ll help the show rank better in iTunes.

Thank you!