Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:47 — 9.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

Day 23 of our 30-Day Micro Leadership Course.

Difficult conversations. How do you handle these? How does your culture deal with them?

Hiding is pretty common. Maybe not physically, but sometimes it could be. Avoiding is hiding. Does that describe how you react to tough conversations?

It’s a common way of handling things. Ignore it – at least head-on – and hope it improves or goes away. Maybe somebody else will say something. Maybe the situation will just get better on its own.

The opposite approach, which I admit I’ve seen only on extremely rare occasions, is what I call “the Kramer approach,” named after the Seinfeld character notorious for blurting out obvious observations that everybody else dare not speak of. Does that better describe how you or your culture handle difficult conversations? You just dive right in without any considerations other than to confront it.

The opposite approach, which I admit I’ve seen only on extremely rare occasions, is what I call “the Kramer approach,” named after the Seinfeld character notorious for blurting out obvious observations that everybody else dare not speak of. Does that better describe how you or your culture handle difficult conversations? You just dive right in without any considerations other than to confront it.

Very few people or organizations, in my experience, embrace the Kramer approach. Most procrastinate dreading the whole thing.

Let’s define what we’re talking about. What is a difficult conversation? It’s simply a conversation you likely know needs to happen, but you dread it.

Maybe it’s coaching an employee on personal hygiene (that example is used quite often whenever I talk with clients about difficult conversations). Maybe it’s correcting poor performance. It could be confronting bad behavior. It could be informing the boss of an error you uncovered. It could be reporting some unethical behavior you’ve witnessed.

Difficult conversations aren’t easy to lump together because they can cover a broad array of topics, people, and situations. That’s why I’ve given them a simple definition as a conversation you know you should have, but you really don’t want to.

I need to reiterate the need for psychological safety again. The safer the culture – the relationship – the easier it is to be candid, which includes being able to say what must be said in order to move forward.

This isn’t about voicing complaints. It’s not tattle-telling. It’s not gamesmanship where we’re trying to look good by pointing out something bad about others. Those are just bad behaviors and no high-performance culture will foster those. This is about being able to muster up the courage to say what needs to be said, even though it’s hard.

The degree of difficulty in having the conversation can be a good thing. Consider the alternative. Suppose you have an employee on your team who has habitual body odor. The fact that you dread having that conversation could mean you don’t want to hurt or embarrass the employee. That’s a good thing. The alternative – the Kramer approach – disregards the person. That’s not a good thing.

Keep in mind how we’re defining leadership – influence and the ability to do for others what they’re not able to do for themselves. When we apply that to this situation we realize as much as we dread having the conversation it’s the best thing we can do for this employee. Delay doesn’t help, except for us to gather our thoughts, rehearse what we want to say, and to make sure we find an appropriate time with this employee to have the difficult conversation.

It’s highly likely the dread and fear are worse than the reality. Through the years I’ve found that almost 100% true. In my head, things typically were much worse than they turned out to be.

Consider the alternative. Consider your responsibility as a leader.

Ignore the body odor problem (or whatever the issue may be). Hope somebody else handles it. That’s not leadership. That’s cowardice.

Hope the person just realizes the problem and fixes it themselves. That’s not leadership. So far they’ve not been able to do that or they’d have already done it. They need somebody to serve them. That’s leadership and courage.

The moment is here. You pull them aside to have a private conversation where you gently, but clearly explain the problem and how you’re committed to help them. You handle it with compassion, but with a firmness to assure them you will do your part to help them remedy this problem. You deal with their embarrassment. You show them the path forward explaining to them this is how all growth and improvement work. You give it your best effort and it goes pretty well, even though it’s admittedly very awkward. You talk about specifics by asking questions like, “Do you have a washer and dryer at home?” Could be they don’t. Could be they don’t even know how to use a washer and dryer. Don’t laugh – I’ve had it happen. I’ve personally confronted this issue on more than one occasion, only to find out the person lacked the lifeskills I took for granted. Nobody had ever shown them these basic life skills, so I took it upon myself as a leader to do that for them. You may think leadership is some grand, big-scale initiative and it can be. But I can tell you when you walk into a laundromat with an employee, armed with a bunch of quarters, and you show them how to do a load of their own laundry…it’s life-changing. For both of you. That’s service. And they’ll never forget it.

That may or may not be your situation, but it does demonstrate a point – avoiding the difficult conversation helps NOBODY. Nobody gets served by hiding, ignoring or putting it off.

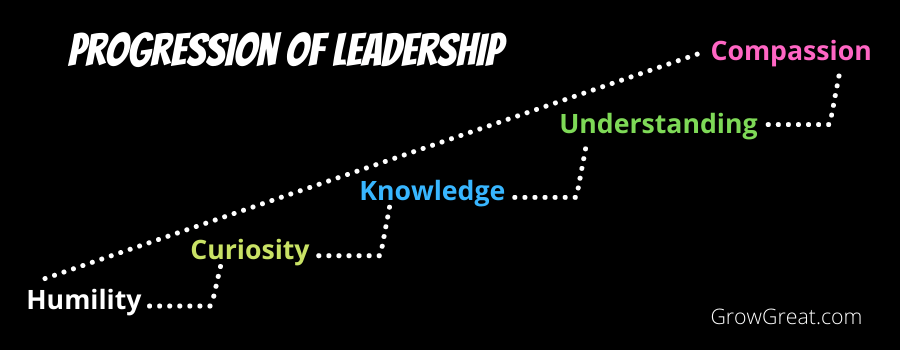

Compassion and leadership share a common theme – a focus on others! Focus the attention on how you can best serve others. It can help you better navigate difficult conversations.

Be well. Do good. Grow great!

About the hosts: Randy Cantrell brings over 4 decades of experience as a business leader and organization builder. Lisa Norris brings almost 3 decades of experience in HR and all things "people." Their shared passion for leadership and developing high-performing cultures provoked them to focus the Grow Great podcast on city government leadership.

About the hosts: Randy Cantrell brings over 4 decades of experience as a business leader and organization builder. Lisa Norris brings almost 3 decades of experience in HR and all things "people." Their shared passion for leadership and developing high-performing cultures provoked them to focus the Grow Great podcast on city government leadership.

The work is about achieving unprecedented success through accelerated learning in helping leaders and executives "figure it out."