Podcast: Play in new window | Download ()

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

Let’s begin by making a distinction between MANAGEMENT and LEADERSHIP.

We manage processes, workflows and systems. We lead people. Effective business or organization building requires both. That doesn’t mean one person – the same person – has to provide both. We celebrate the leader who is an equally capable manager, but quite often the skill set for one is very different than the skills required for the other. It’s one reason (just one) why you see so many co-founders these days. Ideally, one co-founder has terrific managerial talent while another co-founder has strong leadership skills.

Since today’s topic deals with people, it’s a leadership subject.

THE big people problem is almost always communication. Here’s a sentence I never hear,

“Our communication is so good it can’t be improved.”

Instead, I usually hear,

“Communication is our biggest problem.”

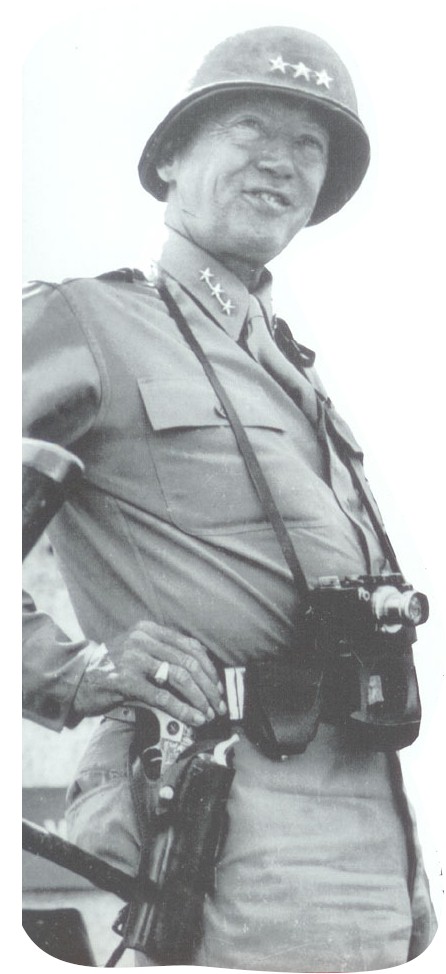

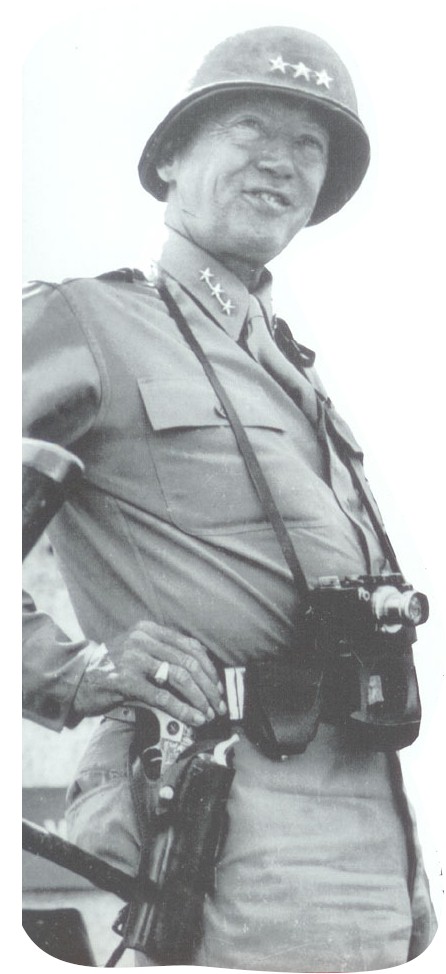

Look at picture of General Patton. Tell me that’s not the posture of a supremely confident leader.

“A good solution applied with vigor now is better than a perfect solution applied ten minutes later.”

Patton was unquestionably one of the most interesting military men in history. His childhood goal was to become a hero. His ancestors were military men dating back to the American Revolution. A strong sense of pride, fierce determination and willingness to go where fighting men went made him popular with the troops.

General Patton was fanatical about having prepared troops willing to execute with excellence. He cared about the process and systems, especially when it came to having his men prepared to fight. Management was important. And he was good at it. But leadership is where he gained his much desired hero status. He knew how to literally rally the troops to go into battle. And he was quotable.

Candid. Blunt. Passionate. Those were qualities the General embraced. Relished even.

Too Much Information

Novice leaders sometimes mistake candid conversations with sharing everything they know. When I’m seated across a first-time leader in their late 20’s I’ll often find myself preaching to them how leadership involves protecting their people. That means, sometimes you must hold your cards closer to your vest and not share too much information.

====================

Coaching Session 8 is a part of my private executive coaching. I’m inserting it here because it’s completely devoted to this notion of leaders sharing too much information and how that’s harmful to your people.

TMI is fairly universal I think. It stands for Too Much Information. And it happens all the time.

It happens at social gatherings. It happens on social media. It happens in texting.

It also happens at work…where it can be devastating.

Okay, let’s eliminate what you may be thinking. I’m not talking about those personal, intimate details people often share resulting is us holding up our hands and saying, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Too much information!”

If I have to tell you how inappropriate it is to discuss really personal details at work, then we need to go back to square one and begin again! It’s not proper to talk about EVERYTHING at work. It’s certainly not proper to SHARE everything at work. Especially intimate details of your life – or of anybody else’s personal life.*

* Listen, as a client, I’m not terribly worried about you doing this because you wouldn’t have likely gotten this far by failing to control yourself, and your discussion points at work…even in social settings around the office. However, even grizzled veterans sometimes, in a momentary lapse of judgment, can say things or ask things that get them into trouble. Guard your tongue.

No, I’m not talking about TMI as we normally think about it – personal details we sometimes share that make others feel uncomfortable. I’m talking about WORK ISSUES that we wrongly share.

You can wrongly share work information in three ways (or perhaps a combination of them):

a. You can share things you shouldn’t share with anybody.

b. You can share things you shouldn’t share right now.

c. You can share things you shouldn’t share with that person.

Timing, the person being told and the fact that it was YOU who told it – those can have a horrible impact on your career and on others, too.

It’s Lonely At The Top

You’re a leader else we wouldn’t be working together. That means you’ve got direct reports and a level of responsibility weightier than the average bear at your workplace. It also means you have to understand and exercise discretion.

Discretion is defined as the quality of behaving or speaking in such a way as to avoid causing offense or revealing private information; the quality of having or showing discernment or good judgment; the quality of behaving or speaking in such a way as to avoid social embarrassment or distress.

Let me expound on those dictionary definitions a bit.

Discretion is the quality of not revealing information that may impede the performance of your employees or direct reports.

Yes, that means sharing things with them that may not serve them well. It means keeping some things to yourself. That’s why the cliche, “It’s lonely at the top” is trite, but true. It is lonely as a leader. Especially when YOU have to keep your mouth shut in order to enhance the performance of your direct reports.

“Well, I would never lie to my people,” you might be thinking.

You should NEVER lie to your people. I’ll go further and encourage you to never lie to ANYBODY. However, just because you know something, or think something, doesn’t mean you should tell it. And if you think that’s lying, then I have no earthly idea how you got this far in your career being that stupid! Call me immediately and fire me ’cause I’m sure I’ll be unable to help you.

Too often leaders forget their pledge of loneliness.

Let me put it into terms you’ll likely understand.

When you were growing up did your parents sit down and tell you all the problems they were suffering? I don’t care if they had marriage problems, financial problems or something else. As a child living at home, were you in the loop on those kinds of things? (For years I’ve asked this and grown increasingly jaded worried that somebody will say, “YES.” Thankfully, so far that hasn’t happened. I hope you’re not going to break my streak.)

I don’t care if you’re a parent or not, you surely understand the wisdom of parents who protect their children from such information. It’s quite literally TOO MUCH INFORMATION for a child to burdened with. It serves no useful purpose to put such things on children. It’s selfish on the part of the parent who would dare do such a thing.

It’s selfish when you do it, too!

Leaders often share things they should not because:

- They lack self-control

- They’re too friendly with staff members

- They don’t maintain professional distance

- They’re selfish and self-centered

- They don’t see themselves as protectors and guardians

- They’re lonely

Yes, there are likely many other reasons you can think of, but this list encompasses most of the ones I commonly see.

True confession (no, this won’t be TMI I promise): I rarely sit down with team members within weeks of initial engagement without unearthing some rather important TMI related issue. It’s remarkable how frequently this erupts into something under the surface…something the leader never intended. People are told things, sometimes in confidence, and the information begins to destroy their ability to do good work. I’ve seen it even destroy their ability to work, period.

People will say to me, “I wish he had never told me that.” Or they ask, “Why would he tell me that?”

I don’t gloss it over, but I don’t go through that list above either. Listen, I know leadership is lonely and I know that a leader’s credibility is always – ALWAYS – on the line. The last thing I want to do is undermine yours IF you’ve been guilty of TMI in the workplace! But I do owe these people a bit of guidance and help and I usually answer these people with honesty about how we’re all people who feel the need to share. Increasingly, with social media and smartphone technology we’re compelled to share more and more. That means, sometimes we share more than we should without even thinking about it. We can all relate to those facts. Then, I encourage them to deal with how this TMI has negatively impacted their work by letting me mediate a conversation about it. Sometimes they prefer to go it alone and talk directly – in private – with the leader. Other times they’re reluctant to even let me help. So important is this issue, I refuse to let up until I gain agreement to handle these things because they grow and fester over time.

I know you mean well, but…

You cannot discuss the poor work or weaknesses of employees with other employees.There are countless variations of this, but you must be so on guard that you refuse to poor mouth people behind their back. This is especially true when you’re dealing with a peer group. For instance, you have 6 direct reports. Casually, in an impromptu meeting with 2 of them you say something about a third member of your team. It’s not flattering. You think nothing of it until you begin to notice a sour attitude of that team member. You may not even remember saying it and you certainly aren’t thinking either of your 2 reports who heard the comment would run to the person to tell them. On all counts…you’d be wrong!

1. You cannot reveal possible changes that might negatively impact a person.

The operative term is “possible.” This is so common that I’ve labored for years with trying to figure out why leaders do it, but so far I don’t have any million dollar insights other than…they’re trying to see how the person might react. That’s not a good enough reason to do it. Let me explain, a SVP (senior vice president) of a division is sitting in your office. You happen to know that HQ is giving serious thought to eliminately this position within that division and reassigning him elsewhere. It’s not yet been decided, but you decide to send up a test balloon by talking about it. You try to couch your words carefully (this is your inner signal that you’re making a BIG MISTAKE). He grows increasingly uneasy in his chair and begins to ask the questions any sane person would.

Now you’re uneasy in your chair and you begin to crawfish and back pedal. The meeting ends and what good have you done? NONE. You’ve now stepped in a pile of crap that will hurt your employee, you and the entire operation. All because you just had to tell him what *might* happen.Here’s the explanation I most often get: “Well, don’t you think they deserve to know?” My answer: “No, they don’t.” For starters, they don’t deserve to know hypotheticals or possibilities unless they’re on the leadership team making such decisions. Secondly, they don’t deserve to be given crappy information. You can’t possibly give them anything to support them when the plan hasn’t even been fully hatched yet. Giving people a “heads up” is wrong. It’d be like a doctor speculating with us about having cancer without having run any tests to first confirm it. It’s just cruel.

2. You cannot blame your boss.

You have a regular meeting with your boss. The boss has made some suggestions – maybe even strong suggestions – regarding one of your team members or perhaps a number of them. At your next staff meeting you lay into your team telling them all about how your boss said this and your boss said that. You think you’re just being candid and open. Instead, you’re being selfish and arrogant. You’re an idiot.And you’re deflecting. You’re blaming the boss in hopes you’re team won’t think it’s YOU who are trying to elevate their performance. It’s your boss who is dissatisfied, it’s not you! You’re in it with your team and if it were up to you, you’d be happy. Blah, blah, blah!

It sounds ridiculous when you read it or hear me say it, doesn’t it? Too bad it didn’t sound as ridiculous when you told your team. Now, it’s like toothpaste squeezed from the tube…you can’t put it back. It’s done now. And it’s gonna cost you some mojo in your leadership because here’s what you don’t know – your team is losing respect for you.

3. You cannot point fingers.

This can be private in one-on-one meetings or it may be in a more public staff meeting. It’s interesting to me how often this happens when the person being targeted isn’t in the room. “Well, that last campaign had some difficulties. Sam knows he should have handled a few things better.” Meanwhile, Sam isn’t even in the building. The leader has just thrown Sam under the bus. Maybe Sam was at fault, but this is TMI and it’s poor leadership. A better option, if indeed Sam’s campaign was a talking point, would be for the leader to say, “Sam isn’t here, but I’ll let you guys know that he deserved more support from me in that last campaign. He and I have talked and we’re both going to make sure we do a better job of it next time.” It’s a completely different message and it’ll make a big difference in how the room sees your leadership.

“He’ll throw Sam under the bus, but he’d never do that to me,” right? See, this is where leaders lose their mind in thinking that TMI won’t hurt them. Only an idiot would think they’re immune from you throwing them under the bus if they see you do it to others. And pointing a finger IS throwing people under the bus. You don’t think so, but your people do.

4. You cannot take it out on your people.

I’ve sat in meetings with people and discussed the meeting privately with both leaders and their direct reports after the fact. The leader sometimes views the meeting as having “gone well.” The direct may say, “boy, he’s sure grumpy today.” Same meeting, two completely viewpoints.

The leader feels the meeting went well completely unaware that his foul mood permeated the meeting. That flat tire he got on the way to work entered that meeting. With frayed nerves he unknowingly barked a bit more than normal. He’s been snappy all morning. The staff has spent all morning trying to figure out why and what they can do to stay out of harm’s way. The lost man hours stack up because the leaders lacked the discipline to protect the work (and his people) from his own issues (professional or personal, it doesn’t matter!).

I can’t possibly review all the possibilities, but hopefully you now have the idea about the negative power of TMI. But before I end let me address one final item that is part of this.

Leaders sometime think they’re helping employees with a bit of “inside” information.

In the quest to let an employee feel closer to the boss, sometimes leaders will draw employees into their confidence. Now, I’m not talking about a person who may be in your true inner circle vital to your decision making. I’m talking about a person who has no need for TMI, a person whose work (and head) may be hampered with TMI.

I challenge you to consider WHY you are telling an employee this information. WHY?

If you are telling them in order to make them feel more like an insider, don’t. There are more effective ways to accomplish that. Namely, by talking with them one-on-one and telling them how important they are to your team, how you value their contribution and how you’d like to place a bit more responsibility on them. Isn’t that going to leave them feeling better than pulling them aside to confide some “secret” thing to them?

Think before you speak. Think before you act. Next time I’m going to talk a bit more about SERVING (I might share that session with you at a future date) your people because it’s an important message that can’t be emphasized too much. It’s a fitting way to end today’s session by reminding you that your job, as a leader, is to help your people do the best work possible. That means you have to guard the information you share with them.

Okay, that’s the end of my executive coaching session number 8. Now, let’s get back to the topic at hand of always being straight with people.

====================

Candid Talk Isn’t The Same As Difficult Conversation, But You Need To Do Both

I don’t think you can have a successful difficult conversation without candor, but that doesn’t mean every candid conversation is a difficult one. Well, it shouldn’t be.

Some leaders (a’hem, “managers”) struggle with difficult conversations. Confronting poor performance, bad behavior, rule violations and other conduct is brutal for them. They get sick at their stomach, break out into a sweat and experience high heart rates. The anxiety can overwhelm some leaders, forcing them to ignore what they know they really need to do. If they have a strong sense of self-examination, they can beat themselves up over their “weakness.” If they don’t, then mayhem creeps into the organization because a lack of accountability becomes more the norm.

My experience in coaching executives indicates that the leaders who struggle with difficult conversations have faulty thinking about the whole process, and the value it serves their people and the organization. Most of us were brought up to be polite. I learned early in life to call adults “sir” and “ma’am.” Even today, if my 2-year-old grandson wants a mint or some candy, I make him say, “Please” before I give it to him. And once he’s got it in hand, I make him say, “Thank you.” That’s ingrained into most of us at an early age. Then we go to school where we’re urged to play nice with others. Fast forward to our first supervisory role at work and we’ve got a lifetime of learning polite manners. Now we’ve got to confront something that involves us calling somebody out. Being impolite. Possibly hurting somebody’s feelings.

WRONG.

Let’s think about what leaders are really doing…their primary purpose. Serving.

Leaders exist to serve their organization by first serving their people, then serving all the other customers. Those customers might be users, clients, partners, suppliers or anybody else. Any leader unwilling to put the employees at the forefront of their attention isn’t worthy of the title. And it can’t simply be lip service. It has to be real, authentic and genuine!

“Do everything you ask of those you command.” – General Patton

Now, let’s consider that difficult conversation. Suppose you’ve got an employee who has slipped into the habit of being tardy. You wonder what’s going on because a week ago she began to come to the office 10 to 15 minutes late. Every single day. This is a new behavior. At first, you figured it was an outlier so you left it alone, but it’s now been 5 days straight of coming in late. You know you need to handle it, but your inner voice is telling you to just let things go and see how it plays out.

Question: How does letting it play out serve the employee?

Answer: It doesn’t. You just feel better not having to confront it. You embrace letting your mind convince you that this otherwise good employee is best served by remaining quiet. But you’re not thinking about the employee or your team. You’re being selfish. You’re thinking about avoiding what you think could be a difficult conversation.

You can *best* serve this employee by holding them accountable, making sure they know a) you’ve noticed their tardiness, b) it’s not acceptable because it will hinder their work, c) it’s not acceptable because it will influence the rest of the team negatively and d) you’re not going to relax your standards for this employee, or for any member of your team. It’s the stuff of higher performance!

The dread is worse than the reality — most of the time.

I’ve had some really difficult conversations in my career. Everything from inappropriate attire to dating amongst co-workers (where inappropriate behavior creeps into the workplace) to drug use, theft and fist fights (all in the workplace). I can give you 3 fundamental keys to being straight with people during difficult conversations:

1. Be prompt.

As soon as you’ve got your facts, engage the employee. Don’t put it off. Don’t overthink it. Don’t talk yourself out of it. But don’t be guilty of the knee-jerk reaction either. And depending on the issue, don’t go in with guns ablazing. Be prepared to listen, but be quick about it.

2. Be understanding, but firm.

Our tardy employee may be going through something you don’t know about. For instance, she might tell you, “I’m sorry I’ve been running late. Last week my mother was placed into intensive care in the hospital. She had a stroke. I’ve been sleeping at the hospital and it’s a longer drive to work.”

Is that an extraordinary circumstance? You bet. And you can handle this however you and your organization see fit, but I’ve had things like that come up throughout my career. My first inclination would be to express my sympathies while encouraging the employee to come to me and keep me informed. I might seek her permission to share this with the rest of the team so others know that her sudden tardiness isn’t the result of her becoming a slackard. I might even work with her to adjust her hours temporarily to fit her current circumstance. I’m not going to let her off the hook and do nothing! That’s not serving her best interests. With a very ill mom in the hospital, how can letting her work habits slip possibly make her life better?

3. Be brief.

These are not times to belabor things. Make the conversation only as long as it needs to be. When I’ve had to deal with internal theft issues the conversations have taken mere seconds. I may have spent weeks fact finding, gathering irrefutable evidence and even lining up appropriate witnesses who can positively confirm the crime. If it’s a petty amount I may reserve the right to simply fire the person and let them walk. In other cases, I’ve notified the authorities and had them at the ready, or even present when I fired an employee. It’s not a long, drawn out ordeal.

Other times I’ve had situations like the worker whose mom is in ICU. Those understandably take longer. The employee is highly emotional, apologetic and feeling badly.

And there are two things I’d encourage you to think about in order to have an effective difficult conversation where correction is the goal. One, you must necessarily make the person feel appropriately uncomfortable. This is the part that curbs a leader’s enthusiasm for having these conversations. If you’re a parent, you already know the value of this part of it. People have to know you’re disappointed and why. That’s part of the process. Without it, you won’t be serving your employees.

When I was 16 working in a hi-fi store I was working the grand opening of a new location. The company had two departments: hi-fi and photo. I knew nothing about photo. An older man walked into the bustling store and I approached him. He asked about some specific piece of photo gear. I told him I worked in hi-fi, but that together we’d find out. I spotted the general manager, Don, across the store. With the shopper in tow, I asked, “Don, this guy is looking for (whatever the item was). Do we carry those?” Don said, “Yes, sir. I’ll be glad to help you” and off they went. I continued to help other customers. At some point, when I wasn’t busy Don spotted me and motioned me to the stock room. We walked into the back store room where Don said, “Randy, do you remember bringing me that shopper looking for some photo gear?” I was a good employee, a top sales guy. There was something about this though that made me uncomfortable. I knew I had done something wrong. I just didn’t know what it was.

“Yes, sir,” I replied. “Do you remember what you said?” he asked. Man, I was stumped. I didn’t have a clue. He could tell I was puzzled. I didn’t answer because I didn’t have an answer, but Don knew me pretty well. After all, we both worked at the main headquarter location so he saw me regularly and interacted me regularly. While I was still pondering what in the world I could have done wrong Don said, “Our shoppers aren’t guys — they’re GENTLEMEN.”

I nodded and said, “Of course. Yes.” And that was it. It only took seconds. I never called a shopper a guy again. That was over 40 years ago, but the impact it had on me was profound. Don served me well. I was a good employee. He was working hard to make me better. And he did. I’ll never forget him for it.

The second component of corrective conversations is something Don did right. He was specific. Clear and specific. I knew precisely what I had done wrong and I knew specifically how to fix it.

Be honest with yourself and your people. Serve them. Serve them well. We’ll continue this next time by going a bit more big picture and talk about how communication determines the culture of our organizations.

About the hosts: Randy Cantrell brings over 4 decades of experience as a business leader and organization builder. Lisa Norris brings almost 3 decades of experience in HR and all things "people." Their shared passion for leadership and developing high-performing cultures provoked them to focus the Grow Great podcast on city government leadership.

About the hosts: Randy Cantrell brings over 4 decades of experience as a business leader and organization builder. Lisa Norris brings almost 3 decades of experience in HR and all things "people." Their shared passion for leadership and developing high-performing cultures provoked them to focus the Grow Great podcast on city government leadership.

The work is about achieving unprecedented success through accelerated learning in helping leaders and executives "figure it out."